The story of who we are—and where we come from—often stretches deeper into time than we imagine. For me, “here” is a crossroads: the Fertile Indus Crescent. Here, the rivers and forests of the Indus Valley connected Persia, Central Asia, and the East. Far from forgotten, it was a thriving meeting ground for traders, farmers, artisans, and storytellers. Civilizations flourished, ideas spread, and lives intertwined.

A few years ago, curiosity about my heritage sparked a journey to uncover the legacy of the Rajputs of India. To guide me, I turned to Professor Emma Wohlart—a Swedish PhD in Classical Archaeology and General Editor of Popular Archeology Magazine.

For me, “here” begins with the Indus Valley Civilization. Thriving around 3000 BCE, it was one of the world’s earliest urban societies. This land of dense forests and fertile plains was nurtured by the mighty Indus River. Born in the Tibetan Plateau, the river flowed through northwest India and Pakistan before meeting the Arabian Sea.

It was in this fertile cradle, thousands of years ago, that my ancestors’ story began—a story shaped by migrations, civilizations, and the endless rhythms of the river itself.

800 BCE to 1 CE: A Crossroads of Kingdoms and Cultures

By 800 BCE, the Fertile Indus Crescent had become a vibrant crossroads of kingdoms and cultures. The great cities of the Indus had faded, yet their spirit lived on. New settlements and ideas emerged.

This was the age of the Mahajanapadas—small kingdoms and republics flourishing along the rivers and plains. They became thriving hubs of trade, governance, and culture.

During this time, Persian influences arrived with the Achaemenid Empire’s expansion under Cyrus the Great. These influences brought advanced administrative systems and expanded commerce. Populations, likely carrying J2a1 lineages, traveled with these networks. Linked to Persian and Mediterranean trade, these lineages connected the region to wider cultural exchanges.

By 200 BCE, the political landscape grew sharper. The Mauryan Empire, under Ashoka, unified vast territories, leaving a legacy of governance, trade, and Buddhism. As Mauryan power declined, new forces emerged: the Indo-Greeks, Shakas (Scythians), and later the Kushans. These dynasties introduced fresh artistic traditions, religious ideas, and trade networks, enriching the region’s already dynamic cultural mosaic. The campaigns of Alexander the Great and subsequent Greek settlements added Hellenistic influence, as settlers—some likely of J2a1 lineage—integrated and contributed to cultural exchange.

Amid this era of change, warrior clans—like the ancestors of the Rajputs—began to solidify their identities. Through oral histories and epics, they traced their lineage and valor, establishing themselves as defenders of dharma and guardians of their lands. From scattered territories to emerging kingdoms, the seeds of the Rajput legacy were sown through battles, alliances, and migration.

1 CE to 300 CE: The Rise of Trade and Cultural Synthesis

The turn of the millennium ushered in a golden age of trade, cultural exchange, and regional transformation. The Fertile Indus Crescent, already a dynamic meeting ground for ideas and peoples, became further entwined with the vast commercial networks of the ancient world. As goods, faiths, and innovations traveled along routes like the Silk Road, kingdoms across Central Asia, Persia, and India grew increasingly interconnected.

Amid this evolving landscape, the Kushan Empire emerged as a formidable power. Originally descending from the Yuezhi nomads, the Kushans forged an empire stretching from the heart of Central Asia to the fertile plains of the Ganges basin. Under leaders like Kanishka the Great, they became champions of Buddhism and patrons of art, architecture, and trade. The empire’s influence was profound—its coinage, artistic traditions, and spiritual teachings reflected a remarkable synthesis of Greek, Persian, Indian, and Central Asian cultures.

The spread of Buddhism during this period further transformed the region. Monasteries and thriving trade routes carried both faith and material wealth, linking cities from the Indus to China. These corridors of commerce ferried spices, textiles, and precious stones, enriching the subcontinent’s economy and establishing its reputation as a crossroads of civilization.

For those connected to J2a1 ancestry, this era brought opportunities for movement and influence. Merchants, scholars, and artisans—many of whom carried lineages tied to Persian traders, Hellenistic settlers, and Central Asian migrants—found a thriving space under Kushan rule. The Silk Road became a lifeline, extending far beyond regional boundaries and enabling J2a1 groups to leave their mark across vast territories.

The “Sisodias of Mewar” trace their origins to the ancient Guhilot clan, a lineage born in the turbulent era of the 6th century CE when Guhil, a legendary prince, escaped his family’s downfall and found refuge in the Aravalli hills. Raised by a temple priest’s daughter, Guhil grew into a warrior and established the Kingdom of Mewar, sowing the seeds of a dynasty that would become synonymous with valor. Over centuries, his descendants weathered invasions, rebuilt shattered strongholds, and forged their identity in fire and blood.

400 to 800 CE: Fragmentation and Warrior Clans

The decline of the Gupta Empire in the mid-5th century marked the end of India’s Golden Age. The realm fragmented under mounting pressure from the Hunnic Hephthalites (White Huns).

In the northwest, remnants of the Saka (Indo-Scythians) endured in Gandhara, Punjab, and Rajasthan. This was despite their earlier defeat by the Guptas.

Amid this upheaval, Yasodharman, a Saka prince, rose to prominence. In 528 CE, he defeated the Huns and reclaimed Malwa, becoming a symbol of resilience.

During this time, smaller warrior clans began carving out their identities. Among them were the Guhilots of Mewar. The legendary Guhil founded the Kingdom of Mewar around 580 CE. His descendants carried forward a warrior legacy, forged in the rugged hills of the Aravalli Range.

By the early 8th century, the first waves of Islamic expansion reached India, led by Muhammad bin Qasim of the Umayyad Caliphate. However, resistance from rising Rajput clans, including the Guhilots, stalled further conquests. Among these defenders stood Kalbhoj (Bappa Rawal), who united neighboring clans, laid the foundation for the Mewar Dynasty, and established his legacy as a protector of the land.

The period from 400 to 800 CE thus witnessed the rise of regional warrior powers whose valor and resilience shaped the foundations of the Rajput states that would dominate Indian history for centuries.

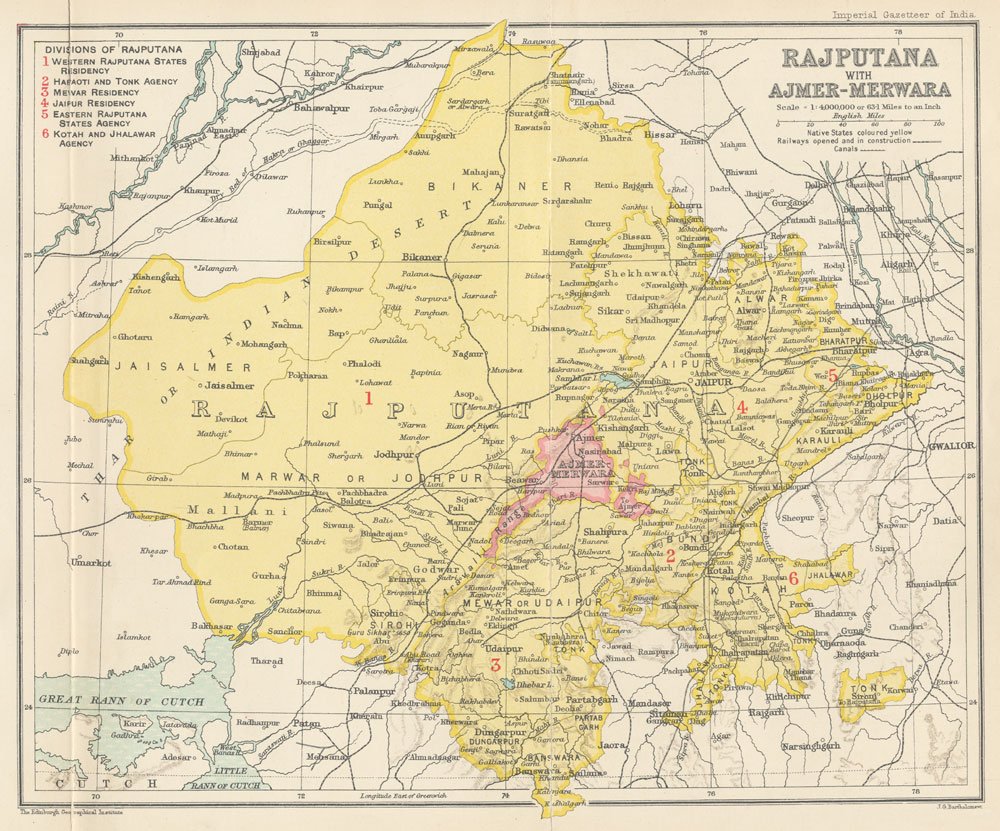

800 to 1000 CE: The Rise of Rajput Power

The early medieval period saw the Rajput clans emerge as powerful regional forces across northern and western India. As the Gupta Empire’s influence faded, smaller kingdoms and warrior clans—like the Guhilots of Mewar—began consolidating power. These clans, tracing their lineage to ancient traditions and valor, capitalized on the political fragmentation to establish their dominance.

By the late 8th century, Bappa Rawal, a legendary figure of the Guhilot dynasty, rose to prominence. Uniting Rajput clans in Rajasthan, he led successful campaigns against Umayyad forces advancing from Sindh. Under his leadership, Mewar became a bastion of resistance and a symbol of Rajput honor and resilience, holding back the tide of Islamic expansion into central India.

1000 to 1200 CE: Rajputana in a Shifting Landscape

The turn of the millennium brought new challenges as Turkic and Central Asian forces began their incursions into the Indian subcontinent. In this era, the Rajput states—now firmly established in regions like Rajasthan, Gujarat, and central India—fought fiercely to defend their territories.

The Guhilots of Mewar, alongside other Rajput clans such as the Chauhans and Pratiharas, became known for their relentless resistance. The rise of powerful Rajput strongholds, like Chittor, symbolized both their military prowess and cultural flourishing. Temples, fortresses, and oral epics from this period celebrated their warrior ethos and their role as guardians of dharma.

However, the increasing pressure from Mahmud of Ghazni’s raids into northern India signaled the shifting power dynamics of the region. The Rajputs—though formidable—were now at the forefront of a changing landscape that would shape their destiny in the centuries to come.

1200 to 1600 CE: Rajput Defiance and the Age of Empires

The defeat of Prithviraj Chauhan in 1192 CE marked the rise of the Delhi Sultanate, ushering in Turkic dominance over northern India. For the Rajputs, this era became one of fierce resistance, as they defended their lands and identities against foreign rulers.

At the forefront of this defiance were the Sisodia Rajputs of Mewar. In 1326 CE, Hammir Singh reclaimed Chittor, restoring Rajput sovereignty and laying the foundation for the Sisodia dynasty’s enduring legacy of valor.

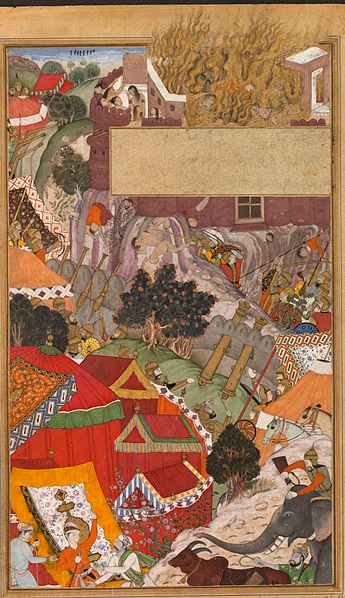

The 16th century brought new challenges with the arrival of the Mughals. Rana Sanga, Mewar’s legendary leader, united Rajput clans to challenge Babur at the Battle of Khanwa in 1527 CE. Though defeated, Rana Sanga’s courage and vision inspired generations to resist Mughal dominance.

By 1568 CE, Akbar’s siege of Chittor forced Rana Udai Singh II to relocate the capital to Udaipur. From this new stronghold, the Sisodias regrouped, refusing to submit. It was in this crucible of struggle that Maharana Pratap, Udai Singh’s son, rose to prominence. At the Battle of Haldighati in 1576 CE, Maharana Pratap defied overwhelming Mughal forces, his guerrilla warfare reclaiming parts of Mewar and transforming him into a symbol of Rajput independence.

1600 to 1800 CE: Rajput Migration, Transformation, and Legacy

The late 16th and 17th centuries tested the endurance and resolve of the Sisodia Rajputs of Mewar. After Chittor fell to Akbar in 1568 CE, the Sisodias, led by Rana Udai Singh II, moved their capital to Udaipur. This defensible city became their stronghold. From there, they continued to defy the Mughal Empire. They waged battles that cemented their reputation for resilience. However, by the late 17th century, Aurangzeb’s rising power brought new challenges to Rajput territories.

By 1679 CE, Aurangzeb exploited internal Rajput rivalries, intensifying pressure on Mewar. The ceaseless cycles of war, betrayals, and shifting allegiances weighed heavily on the Sisodia clans. It was in this period of turmoil that Raja Gulab Singh, a Sisodia prince, made a decision that would alter the course of his people’s history. Tired of the endless conflict over Chittor and Mewar, Gulab Singh led a migration of Sisodia families 800 kilometers north to the lush plains near the Beas River in present-day Ludhiana.

A personal Journey

The Beas region offered peace and refuge. The land was already home to diverse communities—Jains, Hindus, Sikhs, and Lodhi descendants. It became a melting pot where the Sisodias could rebuild. Once a thriving Lodhi outpost, Ludhiana fell to the Mughals in 1526 CE. Yet, its multicultural harmony made it a fitting sanctuary for the weary Rajput migrants.

Between 1679 and 1684 CE, Gulab Singh made a profound choice. To secure stability for his people under Mughal rule, he embraced Islam and took the title Gulab Khan. One can only imagine the weight of such a decision. To set aside centuries of tradition must have been overwhelming. Yet, the warrior ethos of his ancestors remained. Perhaps Gulab Khan saw transformation as transcendence. It was an evolution—one that preserved the Sisodia spirit for a new era.

His descendants thrived in this fertile land. Gulab Khan’s son, Mohammed Mehr Khan, and later his grandson, Mohammed Massania Khan, carried forward their legacy. It is here that history becomes personal. Massania Khan, my grandfather’s mother’s great-grandfather, connects the past to the present. The J2a1 lineage once carried by Persian merchants, warrior princes, and Rajput rulers now echoes through generations. They adapted, migrated and thrived.

More to the Story of Gulab Khan

The Sisodias’ story is more than battles and migrations—it is one of resilience. From Mewar’s rugged hills to the Beas’ fertile banks, their journey reflects survival, identity, and an unyielding drive to forge a legacy.

If you liked this article you may be interested in reading the following:

Wikipedia Page on Sesodia Rajput.