This is not to say that the experience is entirely trouble free. NASA’s Mars lander mission has a 50% success track record so far. But this week’s mission has nudged the ratio higher.

NASA’s InSight spacecraft not only survived its descent through the thin atmosphere of Mars and successfully landed on the planet’s surface but it also send back its first signals and image back and is well positioned to begin to take Mars’s heartbeat in the next few months.

The lander is accompanied by two tiny satellites. These CubeSats caught and relayed InSight’s first signal to Earth, along with a bonus: a first picture of the terrain where the lander will place its two instruments.

NASA engineer and project manager Tom Hoffman (3L) and his team give a press conference after the successful landing by the InSight spacecraft on the planet Mars.

Although the picture is obscured by motes of dust on the camera, the terrain looks promising, says Rob Manning, chief engineer at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) here.

The descent took just over 6 minutes as what was described as the “7 minutes of terror” made famous by the Curiosity rover. After deploying its parachute, InSight discarded its heat shield and extend three legs. A belly-mounted radar sensing the approaching ground managed the decent through parachute and 12 thrusters to slow the lander’s descent to just over 2 meters per second before it touches down.

NASA scientists chose InSight’s landing zone, the vast and dull Elysium Planitia, because they’re interested in Mars’s interior, not its surface. Rocks on the surface could complicate placing the lander’s two primary instruments—a sensitive seismometer and a heat probe—directly on the surface with a robotic arm. It will take several months for the InSight team to choose where to place them. The process mirrors selecting a landing site, and both endeavors have been led by the same JPL scientist, Matthew Golombek. “It’s pretty simple,” he says. “We don’t want a rock underneath. We don’t want a slope that’s too steep. We don’t want underdense material for it to sink into.”

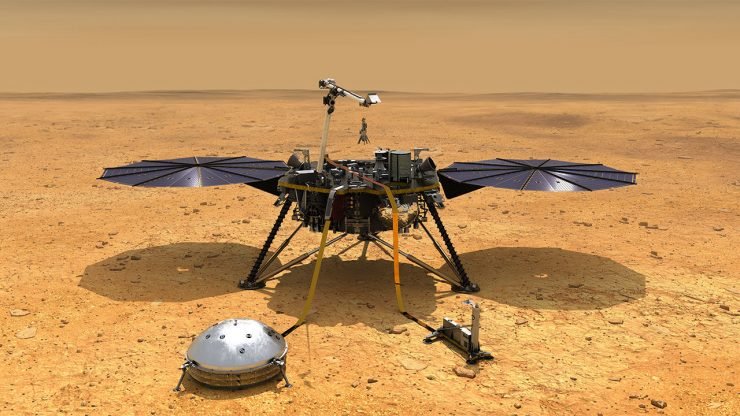

Once mission managers are ready, InSight’s robotic arm will pluck the volleyball-size seismometer from the lander’s deck and place it on the ground, with its power provided by a tether. The arm will then place a wind and heat shield on top of it like a bell jar. The station, developed by French partners, will catch rumbles of marsquakes, important for interpreting the planet’s interior. To avoid the wind vibrations that could trip up its measurements, it will be placed as far away from the lander as possible, up to the arm’s limit of some 1.5 meters away.

The heat probe, developed by German partners, will be deployed soon after. Over the course of a few weeks, it will drive a rod 5 meters into the surface with thousands of strokes of a tungsten hammer, slipping around small rocks—and hopefully not hitting large ones. The heat probe will measure how much heat is escaping from the planet, and how quickly—a clue to when it was most volcanically active. But if there’s only one ideal instrument site, the seismometer takes priority, Golombek says, as it is InSight’s primary scientific payload.

Once all this work is complete, InSight can finally get down to business, using the 50 to 100 marsquakes it might see over its 2-year primary mission to reveal the dimensions and composition of the martian interior—and, in turn, the story of its creation.

Feel free to click here if you are interested to read a more detailed account about the landing Source link