Going through old family documents I, discovered some old papers belonging to my grandfather. Included were papers relating to his education and work; photographs, news clippings and comments from his peers in industry.

It is difficult to write about a man who has been personified in my psyche as the yardstick of success, yet at the same time this was an excellent opportunity to know him in light of his achievements that otherwise I would have not had the chance to.

Born in Patiala, India to Khairuddin Ahmad (my great-grandfather) and Fatima Begum Javed on August 17th 1912, Badruddin Ahmad (my grandfather) was one of the unsung heroes of civil aviation. It could easily be said that he set the cornerstones of the industry before it was even an industry – especially in South Asia.

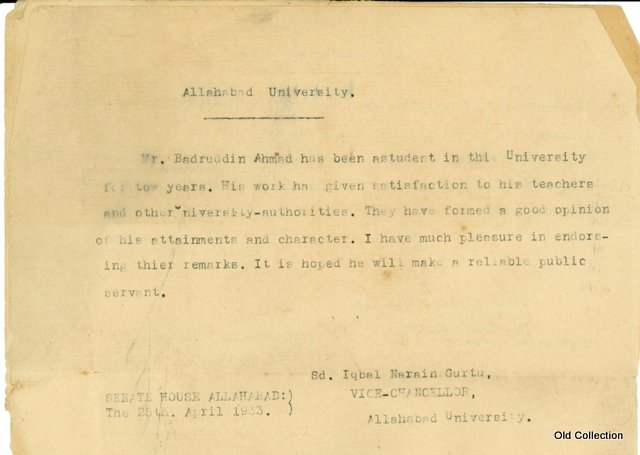

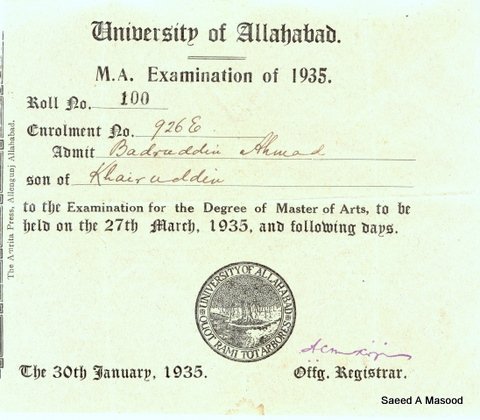

The eldest of five siblings – three sisters and two younger brothers – he was one of the first from his generation to complete a college degree in mathematics with specialization in advanced astronomy from University of Allahabad in 1935. Back in the day University of Allahabad was referred to as the “oxford of the east”.

It was incredibly interesting to note that the first commercial flight in India was from Allahabad to Niani in 1911, the industry grew dramatically thereafter. As a star-gazer, I can’t help but wonder how it must have been, where once uninterrupted skies were now marked by flying machines: a new technology, a new marvel coming within the reach of a common man.

Given his passion for the Civil Aviation Industry, I am sure that it was a dream seeded as a child growing up in changing times.

After his graduation he joined the British Indian Government’s Air Ministry, in a department that was responsible for seaplane docking and later construction of aerodromes. Some of the documents revealed that he played a pivotal role during the Second World War (WWII) in administering the operations of civilian and military traffic through the Indian Subcontinent. As years passed he went up the ladder and later headed the Administration Department within Civil Aviation.

After WWII, he was heavily-involved in the development of postwar aviation plans and he oversaw the planning and construction phases of several runways and airports. The assets developed by him were transferred to the civil authorities, leading to the advent of the Civil Aviation industry under the 1944 Chicago Convention.

Once the partition of the British India was finalized he worked on the split-up of the British Indian Civil Aviation and after the partition, he drafted the plans for civil aviation in Pakistan and implemented pioneering work in establishing the Department of Civil Aviation in Pakistan.

His CV and other documents show that he was responsible for a lot of work in the establishment of Pakistan International Airlines and was director in charge of the construction of various civil aviation works such as non-military jet runways and airports.

Among other things in his capacity of Director of Civil Aviation for the Government of Pakistan, he drafted government policy on the subsidization of flying clubs; licensed many civil pilots, ground engineers and navigators; and progressed the selection and training of pilots and ground engineers. This information comes from his CV, which is mercifully still intact.

In 1955 he was elected member of the British Institute of Transport an organization representing the professionals of the aviation industry.

He represented the nation of Pakistan on many occasions on international civil aviation forums, and represented Pakistan four times in the UN sponsored General Assembly for International Civil Aviation.

In 1959 he was elected by unanimous vote Chairman of the Joint Middle East and South East Asia Air Navigation Conference to lay down the rules for Jet Aircraft operations.

Later in the same year he was honored by the Government of Pakistan with Tamgh-e-Qaid-e-Azam (Medal of the Great Leader) for academic distinction and rendering dedicated services with selfless devotion in public service.

In 1962 he was given the additional appointment of Chief of Administration with the status of Additional Director in the Pakistan Meteorological Department and held these positions till he retired as the Director General of Civil Aviation.

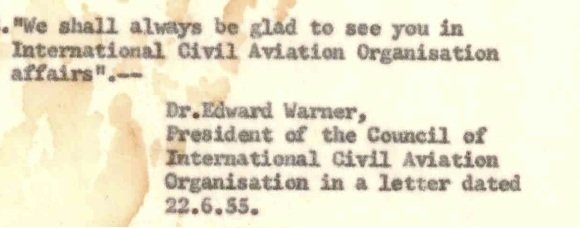

His work in Civil Aviation drew a lot of praise from peers and other pioneers, on one occasion Dr. Edward Warner an American aviation pioneer, and the founder and President of International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) the body that regulates all of world’s airlines, said “we shall always be glad to see you in ICAO affairs”.

At the seventh ICAO Generally Assembly, Sir Fredrick Tymms K.C.I.E, a World War I veteran of the Royal Flying Corps, member of the British Aviation Mission to the USA, and then later Director General of Civil Aviation said “Mr. Ahmad has done great credit to Pakistan in this ICAO General Assembly”.

Establishing air routes and airspace access over countries that often times were not on friendly terms with each other was no easy business. It required diplomacy and the building of utmost rapport, and this is perhaps why at the conclusion of one of the 9th conference the delegate of France moved a motion that stated, “. . . everyone realized the continuing efforts of the Chairman during the past four weeks, not only in the Steering Committee but also in his activities in the Technical Committees and Working Groups. A Large part of the success of the meeting was due to Mr. Ahmad”. The resolution was seconded by the delegate of USA and adopted by acclamation (unanimous vote of confidence).

During his three-decade-long career, he never took sick leave or a vacation other than national holidays and believed that he would miss out on Aviation if he was not there at its helm.

A true Civil Aviator by heart and soul, he once said to my father “always do what you love, even if it means becoming a plumber or a cobbler, because that is the only way to guarantee the work you do would be of utmost quality and everyone appreciates good quality”.

His work meant a lot to him, his passion for it is testament to it – but he was even more.

He was able to read, write and speak English, Urdu, and Farsi (Persian) fluently and was well conversant in Arabic, French and Italian.

A true admirer of Allama Iqbal, he had committed most of Allama’s work to heart and wrote extensively about him and his philosophy, becoming one of the first lifetime members of the council of Iqbal Academy.

If there was anything as important as Aviation it was gardening and photography, some would say his true passion was gardening and photography. He was a fellow of the Royal Horticultural Society and the Royal Rose Society.

Co-founder of the Horticultural Society of Pakistan, where he also served as Vice President between 1959 and 1961. During this time, he introduced the Rubber Plant (Ficus elastic) in Pakistan and received recognitions and awards for Crotons and Carnation cultivations.

During his life he wrote more than 3,000 articles on gardening and photography that were published in Dawn (Pakistan’s English daily), Mirror Magazine, and publications and journals of the Royal Rose Society and the Royal Photography Society.

I remember visiting him during his last days and standing outside him room while my father spoke to him.

He had asked my father to put his arms around him to squeeze him with all his strength, my father did put his arms around but did not squeeze, expressing concerns that he may hurt my grandfather in his frail condition to which my grandfather replied, “I am in a lot of pain, I do not think there can be more”, and then he said “I do not have a house or any property to my name – curse of an honest man, I don’t want you or your brother to be sad that I am leaving with you nothing, this is all temporary, I pray that you and your brother succeed and always have a house of your own”.

He died the next day on March 19, 1981 and had $317 in his account and no other property. He did leave a priceless legacy: have few principals and never compromise them, money is of no value when it comes to integrity and honesty, and that the world kneels before knowledge in awe.

On his passing The British High Commission wrote to the Government of Pakistan with the suggestion that it dedicate a Horticultural Library to his name. A million-pound investment for books was offered in exchange. Sadly, Pakistan’s volatile political situation at the time meant that the proposal became a low priority and was eventually lost in red tape.

NOTE

Badruddin Ahmad by Mani Masood is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

The information on this page along with its associated images, media and graphics can be reproduced for commercial and non-commercial use, as long as it is passed along unchanged and in whole, with credit to appropriate references.